savor

Mindful Eating, Mindful Life

savorthebook.com

Read More About

Mindful Eating

Mindful Living

Weight Loss

Exercise

Meditation

Farm-acies

“More Matters;” “Fill Half Your Plate;” “Go for Color.”

Phrases like these, developed and disseminated by public health advocates, have become the rhetoric in nutritional guidance surrounding the consumption of fruits and vegetables—and for good reason!

Numerous scientific studies show that a diet rich in fruits and vegetables can lower blood pressure, reduce risk of heart disease and stroke, may prevent some types of cancer, lower risk of eye and digestive problems, and have a positive effect upon blood sugar which can help keep appetite in check (ultimately lending a hand to weight management). Moving beyond the individual, we also know that a plant based diet full of fruits and vegetables is also good for the health of the planet.

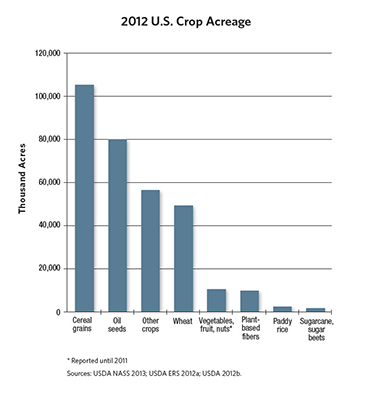

With such promising benefits, it makes sense that the current recommendation is to “fill half your plate” with tasty colorful fruits and vegetables. Unfortunately, the current landscape of U.S. farms is severely misaligned with this public health message, as only two percent of cropland is dedicated to producing fruits, vegetables, and nuts.

This figure may come as a surprise since crop production is the third-largest use of land in the United States (after forests and grassland, pasture, and range), taking up 408 million acres—roughly 18 percent of the country’s land base. So why such low fruit and vegetable production? According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, we have found ourselves in an “unhealthy farm landscape:”

“Among U.S. crop sectors, cereal grains (including corn, sorghum, barley, and oats) constitute the largest harvested acreage, followed by oilseeds (such as soybeans); “other crops” (a catchall category that includes legumes and alfalfa); wheat; and, way down in fifth place, vegetables, fruits, and nuts… Prominent uses of corn and soybeans include fuel (ethanol and biodiesel), livestock feed, and ingredients (such as high-fructose corn syrup) for a plethora of products rightfully referred to as junk foods—highly processed and with low nutrient density.”

Our current farm policies provide farmers with subsidies and insurance who grow these more nonperishable commodity crops, with the catch that they are often prohibited from planting any acreage with perishable fruits and vegetables. This leaves the fruit and vegetable production to hardworking family farms without much assistance, yet they remain dedicated to increasing production.

If production follows demand, then a shift in our focus to fruits and vegetables can spark change in our current landscape. Already, there are pockets of major success throughout the country, such as Los Angeles Unified School District’s mission to support local farms in creating healthier school lunches for their 651,322 children. The initiative was led by the district’s Director of Food Service, David Binkle, who was instrumental in the Los Angeles Board of Education’s 2012 mission to buy more school from producers within 200 miles of the city, with five percent of produce specifically from small- to medium-sized farms. Binkle gave a great TEDx talk this past spring about the initiative, and an LA Times headline from earlier this year sums up the mutual success of the program nicely: “LAUSD food effort makes local farms healthier too.”

Accounts like these are an inspiration to the fact that change is truly possible. The fruit and vegetable portion of our “plate” has immense benefits, and when you look deeply into a bright red tomato or a handful of blueberries that you sourced locally, you can see that farmers are the pharmacies safeguarding the health of Americans.

Photo Credit: Andreas

SAVOR: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life. Copyright © 2025 by Thich Nhat Hanh and Lilian Cheung. All Rights Reserved. Please review our terms of use

Website design

Mary Pomerantz Advertising